The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published the OECD Capital Market Review of the Philippines 2024 in December. The report examines local corporate governance standards, the status of the domestic equity and debt markets and the corporate sector. It makes for interesting reading.

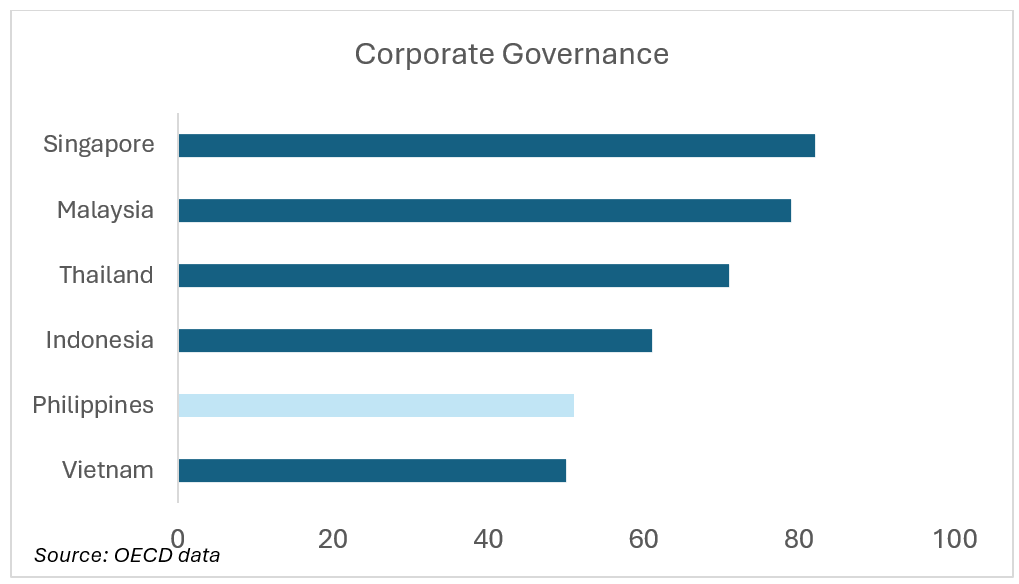

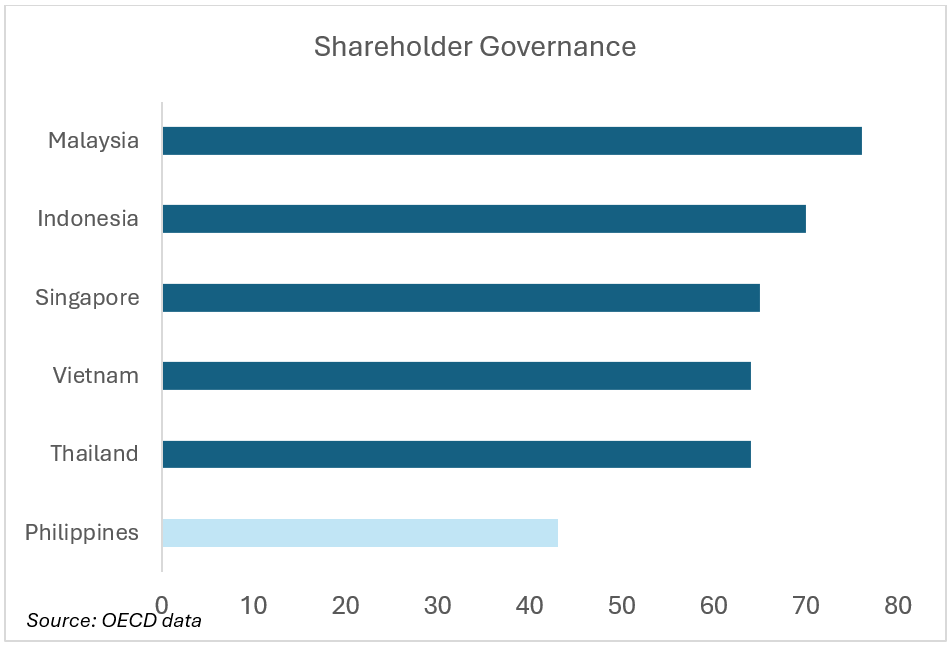

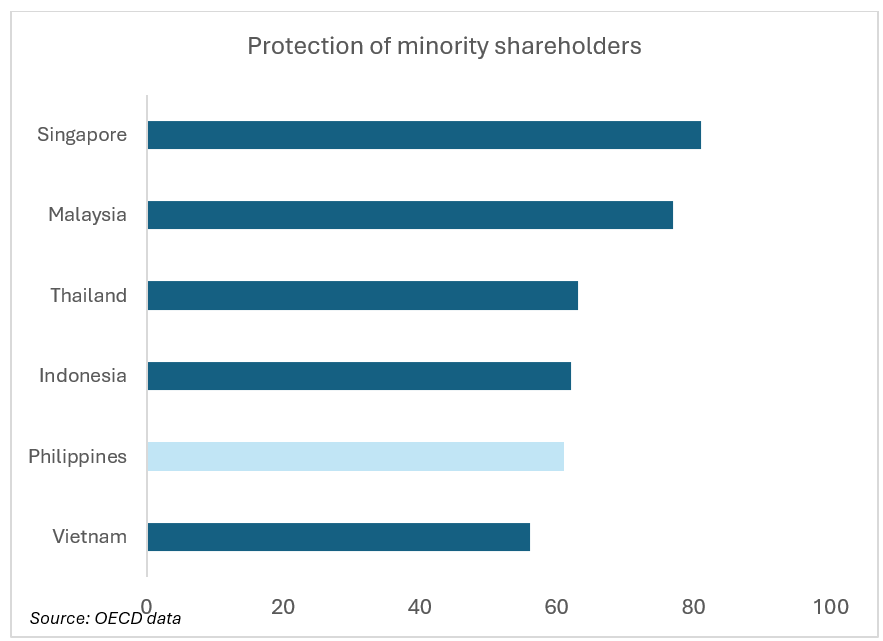

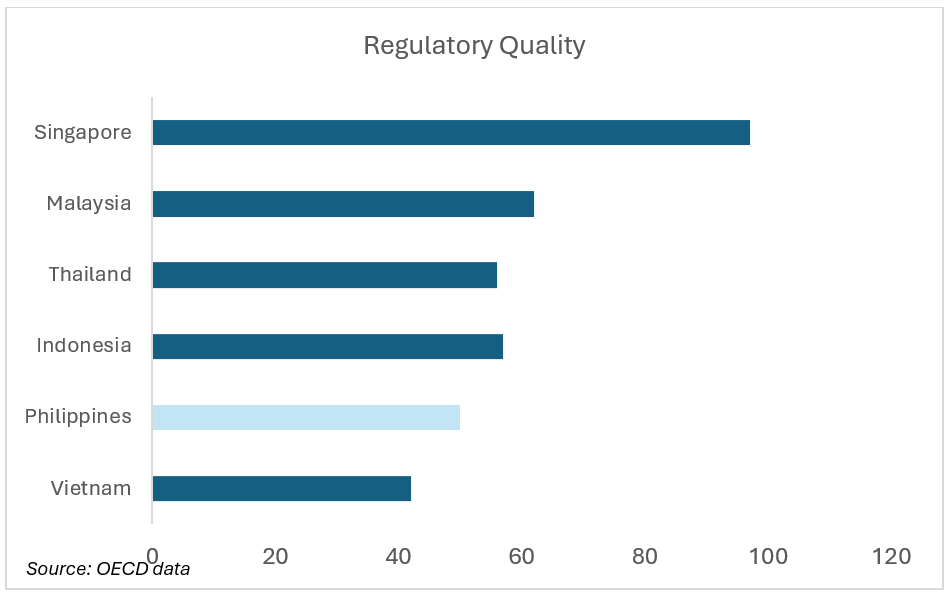

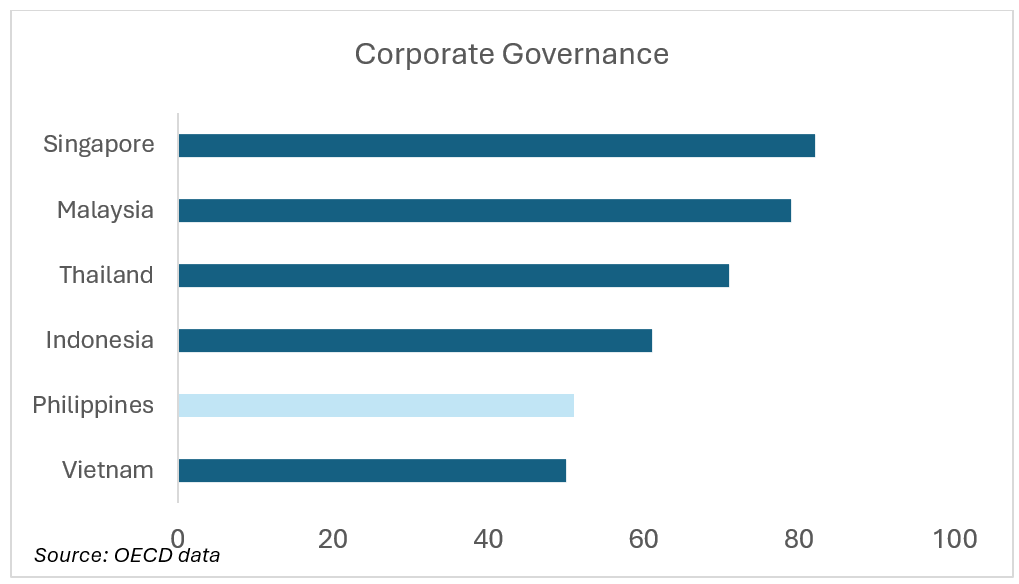

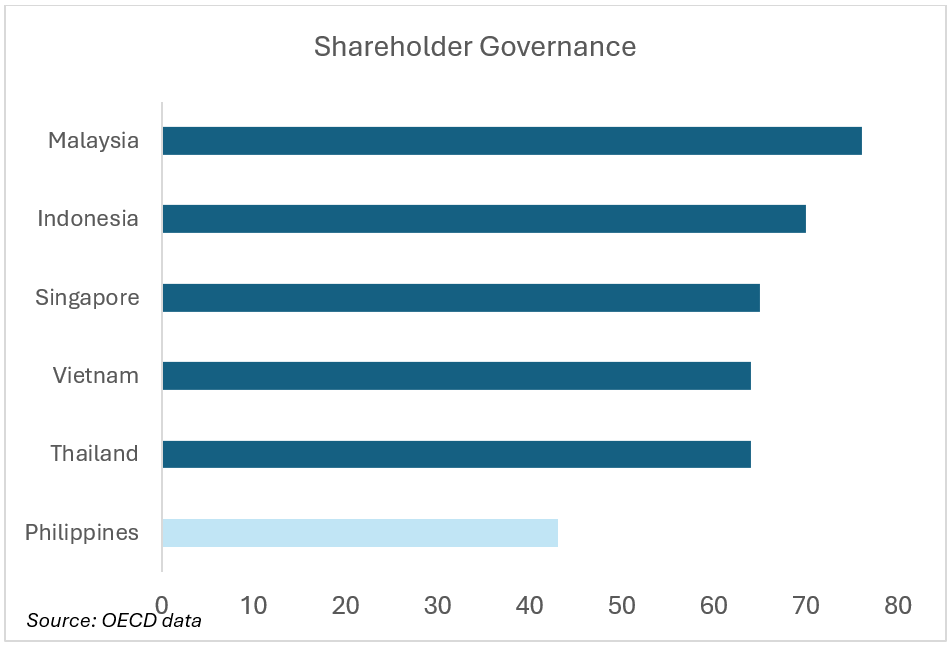

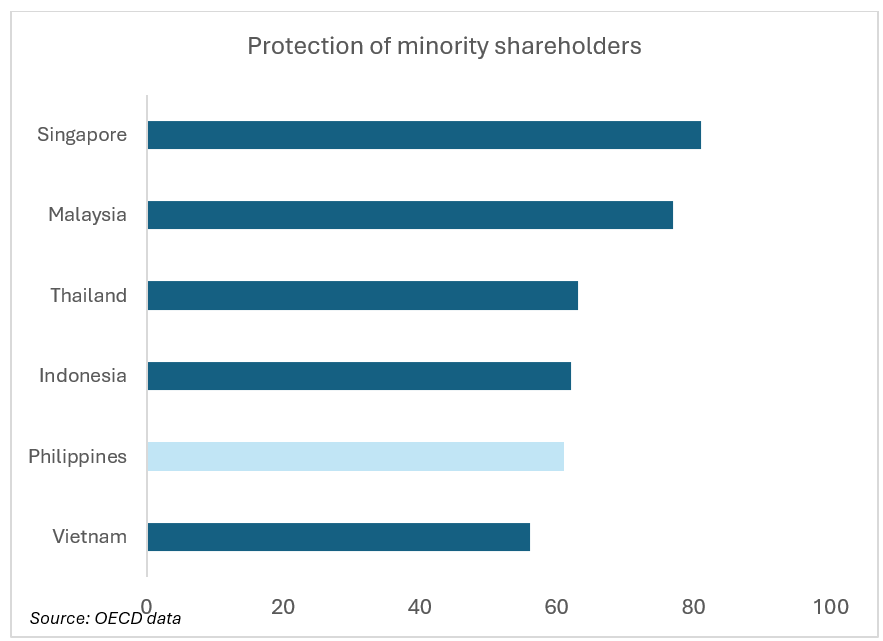

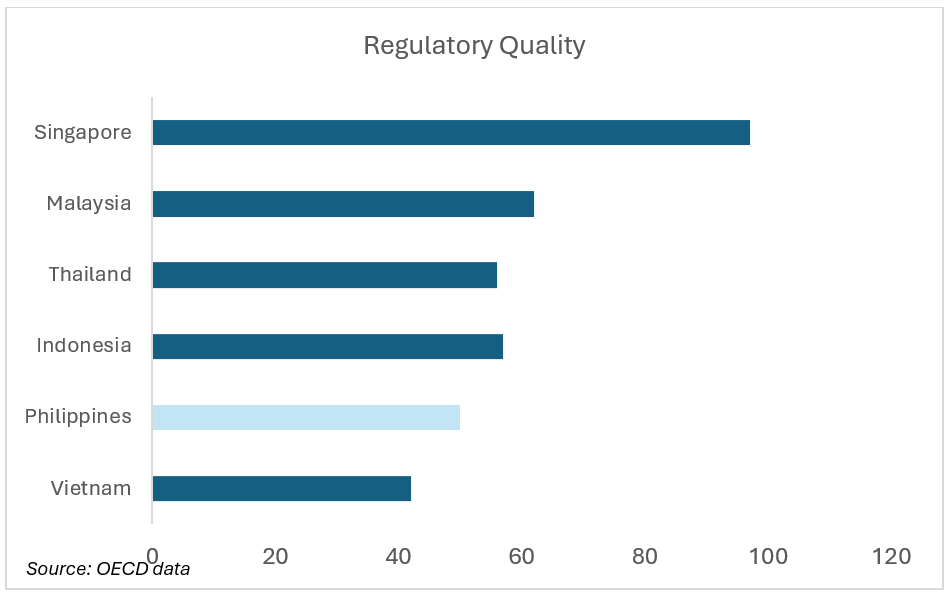

The OECD provides four key governance indicators to assess governance standards in the Philippines and peer markets (see charts below):

In every category, the OECD ranks the Philippines second last or last, behind Indonesia and ahead only of Vietnam in its rating of ASEAN* markets. ACGA’s CG Watch, cited in the OECD review, placed the Philippines just ahead of Indonesia (CG Watch does not cover Vietnam).

While we could perhaps debate the Philippines’ precise rankings in these specific categories with the OECD, what is not at issue is our agreement on the key issues holding back Philippine corporate governance standards and further development of the local capital markets. The OECD’s recommendations to strengthen corporate governance in the Philippines align closely with ACGA’s recommendations from CG Watch:

• Provide local regulators with sufficient resources and a clearer mandate to enforce the CG Code (which itself should be updated)

• Strengthen board independence requirements and enforcement (currently too weak)

• Strengthen rules on related party transactions (some of the weakest in the region)

• Address concerns on cross-shareholdings: (according to the OECD, Filipino companies hold 43% of the listed equity market, the largest share of any investor type and comfortably the highest level of any market in ASEAN)

• Separate the PSE’s commercial functions from its regulatory obligations (which one could say of most exchanges in the region)

• Streamline the SEC’s focus on capital markets regulation and provide more resources for market supervision (i.e.: remove its corporate regulatory function – a proposal ACGA has long espoused)

More than just CG reform

In addition to recommended improvements in corporate governance standards, the OECD review provides several interesting recommendations that highlight the challenges of further domestic capital market reform. These include:

Improving access to and attractiveness of the public equity markets. The Philippines has the lowest number of new listings, and the lowest amount of capital raised of all the ASEAN* markets. The OECD recommends that the listing requirements should be eased, and the current cumbersome process streamlined to encourage more listings at the same time, with a greater focus on shareholder returns, by establishing minimum payout ratios and incentives to companies to deliver greater value to its shareholders. The latter initiative sounds like some of the “value up” proposals being implemented in other Asian markets. It will be interesting to see if such a proposal emerges from local regulators.

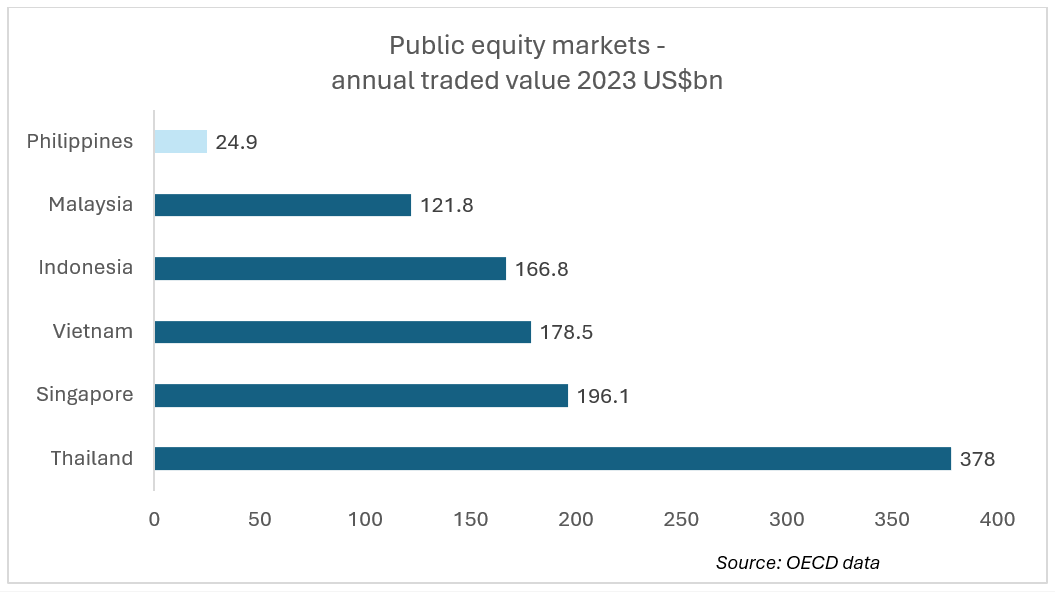

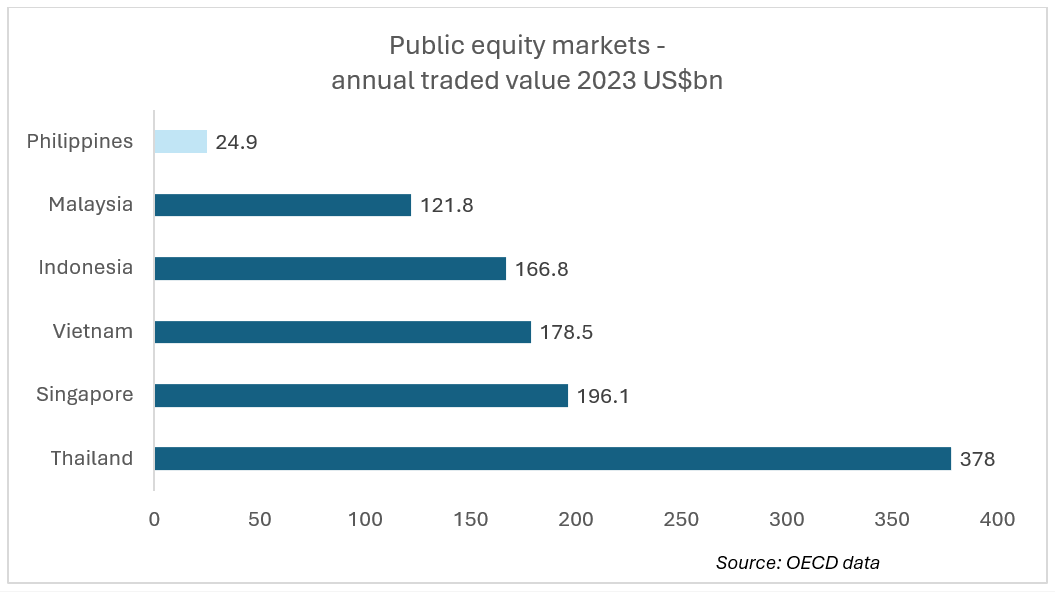

Increasing liquidity in the secondary market. The Philippines currently has the lowest liquidity of all ASEAN* markets (see chart below). OECD suggests incentivizing higher free-float levels, reducing transaction costs for follow on offerings and promoting independent research, market making and derivatives trading.

Increasing long term financing via corporate bonds. The local corporate bond market remains tiny – just 11% of GDP in 2023, according to the OECD. Impediments to increasing corporate bond issuance include time-consuming registration processes - there is no shelf registration in the Philippines - the absence of quality credit ratings agencies and of course, the ubiquity of liquidity within the domestic banking system.

Deepening the investor base. Domestic institutions in the Philippines are small and the existing state pensions and social security systems are limited in the amount of equity in they can invest. Institutional investors owned just 7% of listed companies in 2023, compared with 47% owned by other corporations. Limits on equity ownership by domestic pensions and related institutional investors need to be raised. Collective investment schemes are costly and time-consuming to establish, and rules need to be overhauled to streamline listings. The limited free float in most listed companies discourages many foreign institutional investors from investing in any meaningful way and free float levels must be increased. Notably, unlike all its other ASEAN* peers, the Philippines does not have a single listed state-owned company.

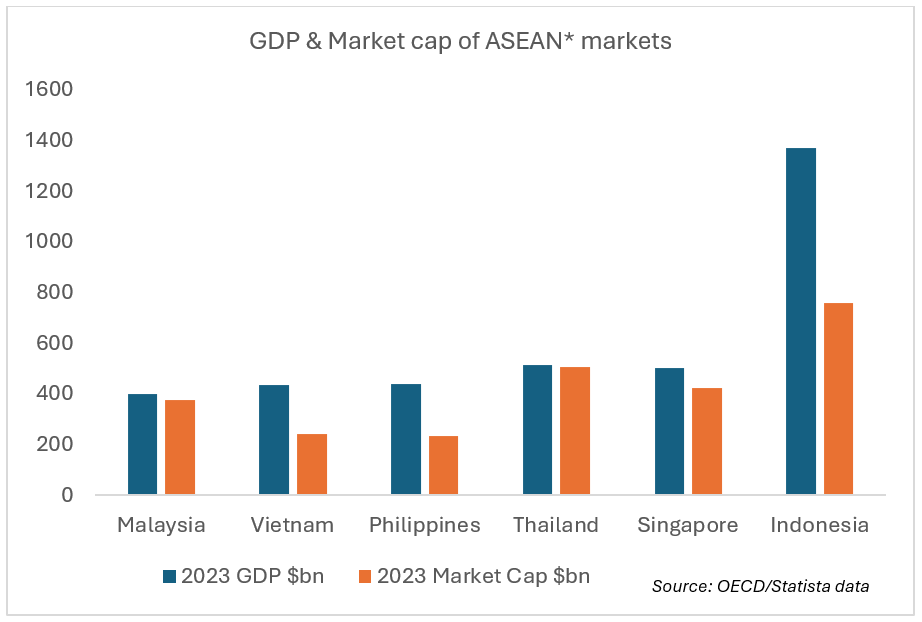

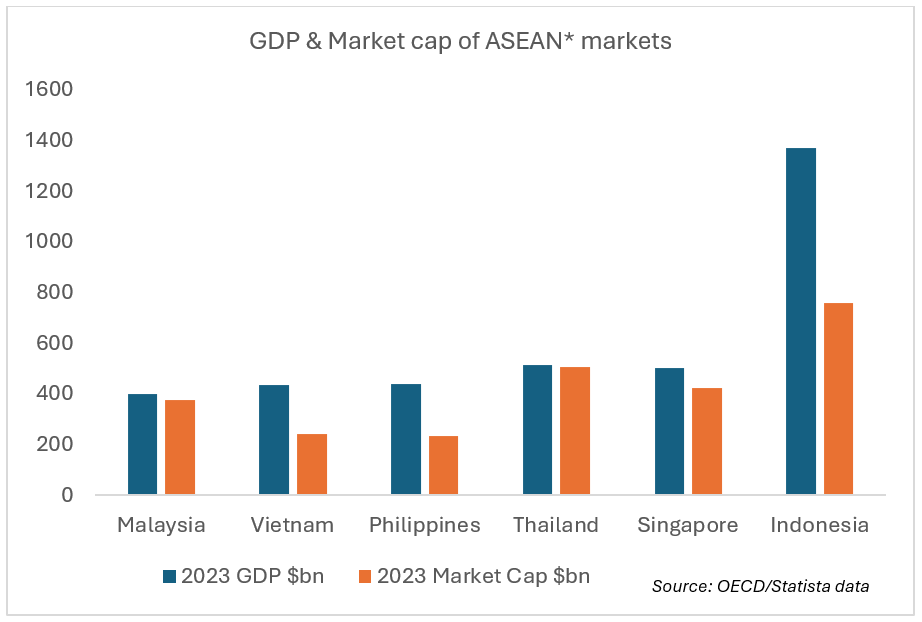

While the Philippines has grown strongly economically in the last decade, its capital markets lag its ASEAN peers on most measures. It has the lowest market capitalization to GDP of any of the ASEAN markets (see chart below).

Meaningful reform is clearly needed and one of the biggest barriers to economic and capital markets reform remains the oligopolistic nature of its economy: the OECD estimates that just 15 major domestic conglomerates accounted for more than 20% of GDP in 2018, a number it acknowledges likely understates the actual economic dominance of these corporations. Meanwhile, the ten largest domestic banks – eight of which are part of family-controlled conglomerates – hold 60% of all banking sector assets.

The Philippines had the lowest market capitalization ($234 billion) and the lowest traded value ($24.9 billion) of any ASEAN* stock market in 2023. While it is not surprising that Philippine companies comprise just 0.7% of the MSCI Emerging Asia index, the lowest of all ASEAN* markets, if the country is to meet the economic challenges it faces and fulfil its obvious economic potential, it must start with meaningful reform of its capital markets.

* Note: ASEAN for the purposes of this article and data cited herein refers to the markets of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

About the Author(s)

Christopher Leahy

Christopher Leahy

ACGA Specialist Advisor, Southeast Asia

Christopher Leahy is Specialist Advisor, Southeast Asia, with ACGA and Managing Director and founder of Velos Research, an independent research and advisory firm that partners with project owners, companies and investors to convert emission-reduction projects into commercial realities. Chris is also an independent non-executive director of Destileria Barako Corporation, an independent distillery and drinks group in the Philippines.