Corporate Governance In Asia: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back?

by Vivian Yau, ACGA

Over the past two decades, the highs and lows, and twists and turns of the corporate governance scene in Asia-Pacific have been tracked by the Asian Corporate Governance Association through its Corporate Governance Watch reports. How has the region fared over the years?

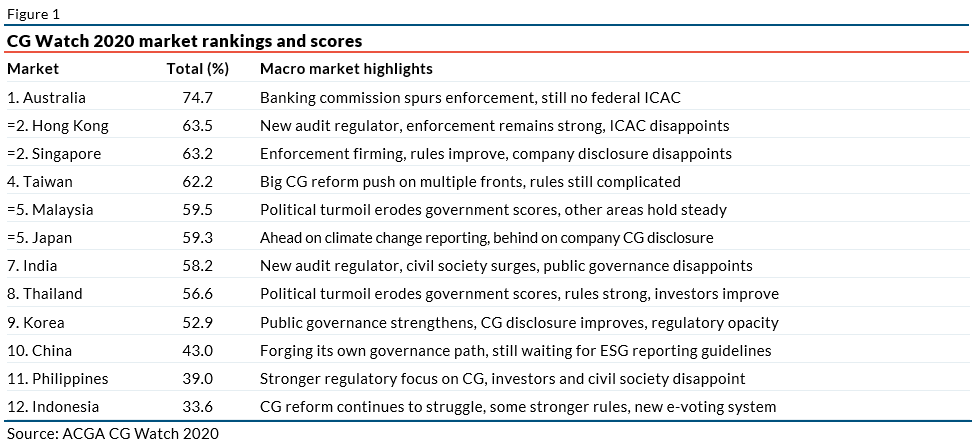

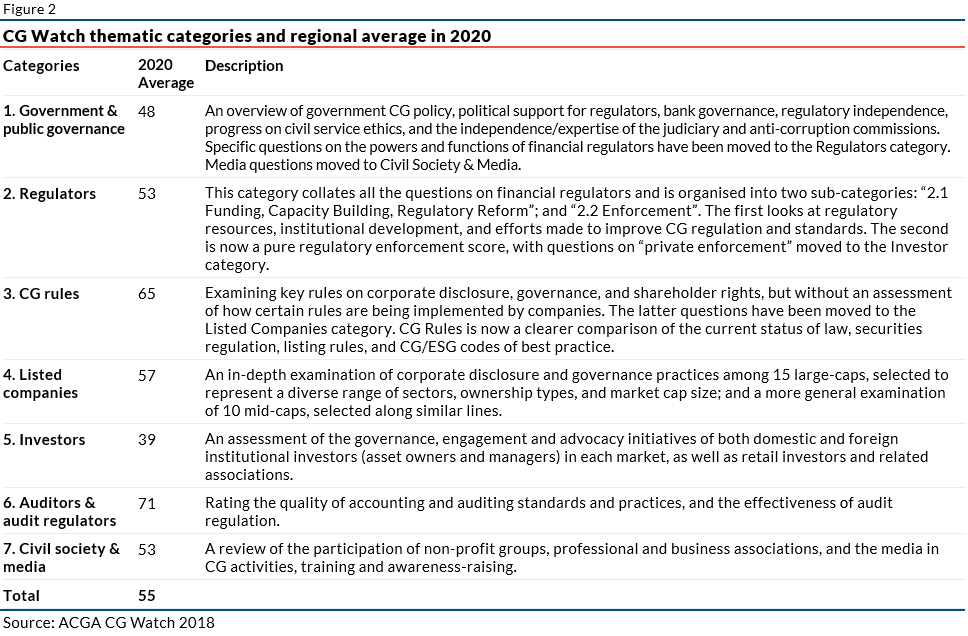

CG Watch is one of the most comprehensive surveys on corporate governance in Asia Pacific. The biennial study comprises two distinct surveys: a market ranking survey on macro corporate governance quality in 12 Asia-Pacific markets, and a separate survey on corporate governance practices of about 1,200 listed corporations across APAC.

The latest CG Watch survey released in May 2021 saw Australia take the top slot, followed by joint runners up Singapore and Hong Kong. Meanwhile, Taiwan and South Korea showed the biggest improvements. Across the region, things are looking up. Highlights of each of the 12 countries are shown in Figure 1.

Progress, however, remains slow in key areas. For example, policymakers shy away from driving the corporate governance agenda, and the impact of regulatory enforcement is limited. Meanwhile, corruption in markets such as Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Malaysia still looms large.

The biggest drag in recent years has been at the hands of market regulators. The loss of the “one share, one vote” principle with the advent of dual class shares (or weighted voting rights, as they are known in Hong Kong) and the introduction of special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) are, in our opinion, major missteps.

On the upside

Substantive improvements have been made in corporate governance and environmental, social and governance (ESG) rules across the region, in particular standards for sustainability reporting, updated CG codes of best practice, and new or revised stewardship codes. Real changes are also evident in the quality of corporate disclosure around climate change and sustainability issues. Audit regulation is also becoming more sophisticated and transparent.

Indeed, CG rules is the second highest scoring category in our survey, after auditors and audit regulators. Australia continues to lead the way, followed by Malaysia and Thailand, which have solid CG rule books, just nudging ahead of Hong Kong and Singapore.

In China, a revised securities law in March 2020 has significantly increased the cost of wrongdoing, with fraudsters now facing a penalty of up to double the amount of ill-gotten gains compared to 5 per cent previously. Changes to Japan’s CG code and stewardship code in 2020 include setting a one-third independent non-executive director threshold for the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime market by April 2022. Korea meanwhile requires its large caps to put an end to single-gender boards by August 2022, as well as requiring issuers to release annual reports before AGMs and follow a new CG reporting template.

ESG standards are also advancing around the region. Hong Kong adopted a newly revised ESG Reporting Guide in 2020 requiring disclosure of the board oversight role in ESG reporting. That same year, Japan published a new Practical Handbook for ESG Disclosure, while Korea announced plans to require ESG reporting by large-caps. Singapore Exchange unveiled its roadmap for issuers to provide climate-related disclosures based on recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures in December 2021.

Listed companies are increasingly focused on how they respond to climate change, with Japan leading the region in this respect. Companies are cranking up the volume in terms of ESG and sustainability reporting, but with the caveat that materiality in general is lacking and the volume of boilerplate disclosures remains high. Of the companies surveyed in the CG Watch research, half the markets were good at disclosing materiality issues when compared to Sustainability Accounting Standards Board standards, including Australia, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand. In Australia, companies went a step further in summarising these materiality issues in the form of a matrix, table or list.

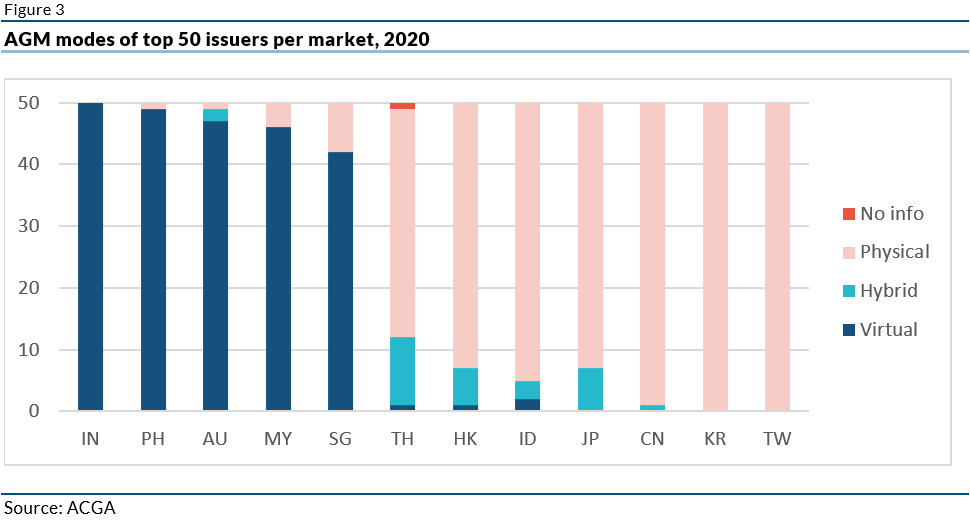

Some issuers also proved nimbler than others when it came to responding to Covid. Five of the 12 markets embraced virtual AGMs. Regulatory rigidity left China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan behind the curve, only allowing hybrid but not fully virtual meetings. Hybrid meetings are where minority shareholders can attend the meeting in person or online, whereas in virtual meetings, directors and company staff may attend, with minority shareholders only joining online.

Another bright spot was found in the upgrade of auditing practices and regulation of the profession in markets such as Hong Kong and India. An independent audit oversight body was established in Hong Kong in October 2019, a good 15 years after Japan and Singapore. India’s new National Financial Reporting Authority meanwhile began investigations into errant auditors in 2019, albeit with limited resources and a court challenge to its powers by one of its targets.

Could do better

A clear strategy for developing corporate governance is, however, still lacking in most markets: a framework that we believe could be a source of competitive advantage. While most Asian policymakers are enthralled with the possibilities of ESG and green finance, their approach to corporate governance is often contradictory. This is evident in policies such as weighted voting rights, which directly undermines good corporate governance, or through apathy toward shareholder rights.

And as regulators increase their enforcement efforts, we find that outcomes are often difficult to track, and a number of markets ultimately fall short. There is a notable regionwide shift from criminal to civil redress, with Thailand and Malaysia leading the charge and Taiwan introducing a new commercial court for civil cases. Australia vowed to up the ante with a “why not litigate” mantra after a dressing down by a Royal Commission report, but this appears to be fizzling out. It is the sponsors, rather than issuer miscreants, who tend to receive the biggest fines in Hong Kong, and insider dealers continue to keep regulators busy in Thailand and Japan but are notably absent in Indonesia and the Philippines.

There needs to be greater clarity on both enforcement data and the funding regulators receive to pursue wrongdoing, along with a more descriptive narrative as to where battles are being won and lost. In Hong Kong, Taiwan and Australia, market regulators publish detailed figures on their operations, with the size of budgets increasing over time and sufficient resources to do their jobs. Other markets are less forthcoming.

Corruption agencies in the region can be prone to selective disclosure of outcomes, possibly indicating that their bark is bigger than their bite. Japan keeps no national statistics on graft at all. It appears that enforcement of corruption has hit a plateau, with few blockbuster cases grabbing the headlines (the one notable exception being the 1MDB trials in Malaysia). Politics, meanwhile, has derailed Indonesia’s once-feared Corruption Eradication Commission (known locally as the KPK), and Australia continues to waver over the need for a federal-level National Integrity Commission. The Philippines, Japan and China still lack an independent agency.

In reverse

ACGA views dual class shares and SPACs as retrograde moves by market regulators. Hong Kong introduced weighted voting rights in 2018 (Alibaba was the first issuer to take advantage of the new regime, listing in November 2019) with certain safeguards for investors, but the fear is that these will be weakened over time, and more companies will choose to raise capital with shareholding structures which are fundamentally detrimental to investor interests. This sets companies down a path of lower CG standards, increased investor and regulatory risk, and weakened market valuations over time.

Many of the weighted voting right companies in Hong Kong are secondary listings, and they receive generous waivers from the Stock Exchange rules, including rules on notifiable and connected transactions, ESG reports and the CG Code.

Dual class shares also arrived in China in April 2018, and the first issuer to debut with this structure was UCloud in January 2020. It took two years before Singapore’s first dual class listing emerged, with the arrival of little-known player AMTD International.

Likewise, SPACs recently arrived in Hong Kong and Singapore, just as US investors’ and regulators’ appetite for these empty shell listings began to wane. ACGA prefers companies to list through the front door and face robust regulatory vetting. Still, Hong Kong – wary of years of backdoor listing abuse in the market – limited the SPAC regime to professional investors only and has a higher minimum fundraising threshold than Singapore and New York. With only 29 approved professional investors allowed to trade the shares of Aquila Acquisition Corp, the first SPAC to list in HK, its debut in March 2022 was somewhat slow.

We remain wary of structural changes to the ecosystem, such as SPACs and dual class shares which have the potential to negate the incremental gains being made to corporate governance highlighted above. Hopefully, the region will deliver greater progress in the coming years.

This article was first published in the Q3 2022 issue of the SID Directors Bulletin by the Singapore Institute of Directors.

Download File Disclaimer

In addition to the ACGA website disclaimer access to the "Members' Area" of the ACGA website is subject to the general disclaimer and content attribution statements below.

General Disclaimer

By logging into our Members' Area you acknowledge that all materials displayed on the site or made available for download are for the exclusive use of ACGA members. You may not share the content with parties outside of your organisation.

Content Attribution

The copyright ownership of all material on our website belongs to ACGA. Should you wish to use any materials in the course of your corporate research, including directly quoting or paraphrasing sections, reprinting, reproducing or the like, we request that you give proper acknowledgement to ACGA and share a copy with us. Please email irina@acga-asia.org.