China’s new draft CG Code: 80% alignment, 20% innovation

by Lake Wang, ACGA

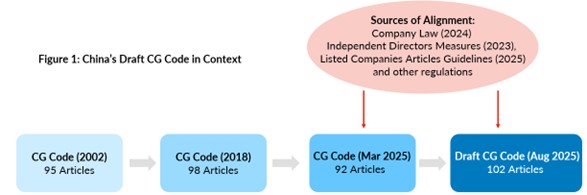

On 25 July 2025, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) released a new draft of the “Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies” (“CG Code”) for public consultation. (1) China’s CG Code has been updated only twice since its introduction in 2002—once in 2018 and again in March 2025, underscoring the importance of this consultation. (2) The March 2025 review was part of a broader overhaul that resulted in revisions to over 80 regulations, harmonising with the changes to the Company Law which came into effect on 1 July 2024.

The CSRC stated that the current review mainly focuses on strengthening the regulatory framework governing directors, senior management, controlling shareholders, de facto controllers and other influential stakeholders, collectively known as the “critical few” (guanjian shaoshu 关键少数). This move is intended to implement the 2024 “National Nine Articles” and recent high-level guidelines on China’s modern corporate system. (3)

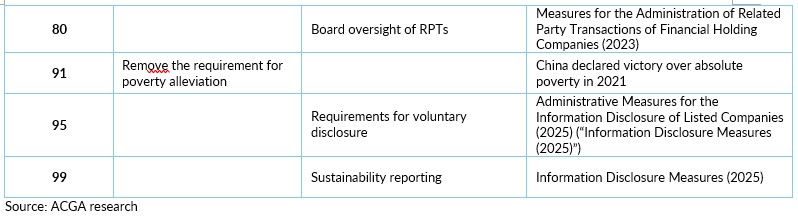

The current draft retains all changes from the March 2025 version. Given this continuity, our analysis here covers changes in both versions. Of 42 amended or newly added articles across both editions, most are drawn directly from the amended Company Law and other regulations. Compared with the March 2025 version, the new draft strengthens accountability for the “critical few” and significantly expands requirements for remuneration (see appendix table for details).

Source: ACGA research

This extensive alignment ushers in some positive changes. Notably, the duties of loyalty and diligence to the company are explicitly extended to controlling shareholders and de facto controllers who act as de facto directors. Issuers are also required to provide justifications and mitigating measures if a controlling shareholder or a de facto controller serves as both board chair and CEO. In China, de facto controllers are individuals and entities that exercise effective control over the company through investment, contracts and other arrangements.

Disqualification criteria for directors and senior executives are introduced. Additionally, their post-tenure obligations and accountability are now required to be clarified in service or employment agreements.

Amid the draft Code’s verbatim alignment with the amended Company Law and other regulations, the remuneration section sets out a number of new provisions. Internationally well-established concepts such as performance-based pay, deferred payment and clawback mechanisms are incorporated into a section which was previously light on such detail. This aspect of the draft Code also includes Chinese characteristics by proposing differentiated remuneration policies for R&D-intensive yet unprofitable companies and top tech talent, supporting the national policy priority of technological innovation.

However, the draft CG Code falls short of enhancing transparency around the Party committee and of aligning the requirements for key areas such as investor stewardship and board diversity with global standards. Undoubtedly, Party leadership has become a fundamental element in the governance of Chinese listed companies. Yet, the workings of the Party committee are not as visible to investors as those of the board. Requiring an annual disclosure on its structure and key activities would provide much-needed transparency.

Secondly, the draft Code’s Chapter Six on institutional investors and relevant institutions, which remains largely unchanged in this consultation, could also be strengthened by explicitly including board-level communication or engagement as part of investors’ stewardship toolkit. Ideally, stewardship considerations and responsibilities would also be mirrored in the sections of the Code relating to obligations of independent directors.

Thirdly, the provision on board diversity, which only encourages “diversity of board members”, still lags behind regional best practices. As a starting point, this could be made more action-oriented by encouraging companies to develop a board diversity policy.

Lastly, we highlight areas for subsequent development and improvement, including shareholder protection in related-party transactions and change of control transactions, sustainability reporting, and board independence and expertise.

Zeroing in on the “critical few”

Nearly one in four of the amended or newly added articles (10 out of 42), including those from the March 2025 update, address the “critical few”, including directors, senior management, controlling shareholders and de facto controllers. Notably, controlling shareholders and de facto controllers are collectively referred to as “dual controllers” (shuangkongren 双控人).

Dual controllers and disclosure requirements

Article 265 of the 2024 Company Law defines controlling shareholders as those who directly hold more than half of a company’s total share capital or who, despite holding less than 50%, can exert significant voting influence. The same article also defines de facto controllers as those who can effectively control the company through investment, contracts or other arrangements.

The CSRC requires listed companies to disclose both controlling shareholders and de facto controllers in their annual reports. For example, at BYD, both the controlling shareholder and de facto controller are Mr. Wang Chuanfu. By comparison, Kweichow Moutai identifies China Kweichow Moutai Distillery (Group) Co., Ltd. as its controlling shareholder, and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of Guizhou Province as its de facto controller.

Refining core duties

The statutory duties of directors—loyalty and diligence—are elaborated in Articles 24 and 25, respectively. In another subtle semantic change, in line with the amended Company Law, the word “prudently” has been dropped from Article 23, which now states only that directors shall “perform their duties faithfully and diligently”. (4)

Aligning with the 2024 Company Law, the draft CG Code also explicitly extends the duties of loyalty and diligence to senior executives (Article 53), as well as to dual controllers who do not hold directorships but actually execute company affairs (Article 67)—dual controllers who, though not directors, carry out directors’ duties.

Constraining dual controllers

Given the prevalence of concentrated ownership in China, the CG Code has traditionally dedicated an entire chapter to dual controllers, covering their relationship with the company and their conduct in areas such as director nominations, related-party transactions (RPTs), as well as other corporate matters. In addition to explicitly extending the duties of loyalty and diligence to some of them, the draft Code introduces the following key provisions:

• Dual controllers as board chair and CEO: If a controlling shareholder or a de facto controller serve as both board chair and CEO, the company should justify these arrangements and outline measures to maintain independence (Article 73).

• Joint liability: Article 67 holds dual controllers accountable if they instruct directors or senior executives to take actions that harm the interests of the company or its shareholders.

• Board oversight of related party transactions (RPTs): The board is required to clearly identify related parties in these transactions and strictly enforce abstention voting rules (Article 80).

Strengthening obligations and accountability

The proposed CG Code requires companies to play a greater role in defining and scrutinising the obligations and accountability of directors and executives:

• At the start of tenure: Companies should specify in service agreements or employment contracts the obligations that directors (Article 21) and senior management (Article 52) continue to have after their departure. These agreements also need to include clauses on holding them accountable and recovering damages for any wrongdoing during their tenure—even after they have left.

• At the end of tenure: Issuers need to review any outstanding obligations and commitments of outgoing directors (Article 30) and senior executives (Article 53), as well as any suspected involvement in violations of laws or regulations during their tenure.

Allocating liability for damages

Article 26 clarifies respective liabilities of directors and the company for damages. When a director causes damages to third parties while performing company duties, the company bears the liability for compensation. (5) However, if the director acts intentionally or with gross negligence, they are also personally liable.

Moreover, directors are personally accountable if, in carrying out their duties, they violate laws, regulations or the company’s articles of association, resulting in damages to the company. Article 54 includes corresponding provisions for senior executives and the company.

Introducing disqualification criteria

The draft CG Code outlines circumstances under which individuals are deemed unfit to serve as directors (Article 20) or senior executives (Article 51). The nomination committee’s gatekeeping role is also emphasised, as it is responsible for vetting director candidates and conducting annual fit-and-proper assessments of senior executives.

In China, the nomination committee is encouraged but not mandatory for listed companies. Where established, the committee must be chaired by an independent director and consist of at least half independent directors.

Addressing remuneration policy gaps – international alignment and Chinese characteristics

The remuneration section in the draft CG Code deviates from word-for-word alignment with domestic laws and regulations while expanding from five to nine articles. So, what’s new?

Most of the updates are straightforward, addressing gaps in China’s CG rulebook. For instance, Article 58 requires companies to establish “remuneration management policies” that cover mechanisms for determining the overall compensation pool, the structure of directors’ and executives’ remuneration, performance reviews, payout processes and clawback provisions. Other key new provisions include:

• Deferring performance-based remuneration (Article 63);

• Clawing back performance-based remuneration in cases of serious misconduct or financial fraud (Article 64);

• The role of external accounting firms in assessing the effectiveness of performance evaluations and remuneration payments (Article 61).

Separately, Article 60, which is uncommon in other markets, permits companies in cyclical sectors to link directors’ and executives’ performance-based pay to the company’s financial performance cycle. (6) If the cycle exceeds three years, companies need to provide an explanation.

Under the same article, directors and executives at loss-making companies with significant R&D activities, as well as those qualified as top tech talent at other companies, may receive compensation under policies not linked to corporate performance. Moreover, Article 59 requires companies to reasonably determine the pay ratio between directors/senior executives and ordinary employees. (7)

This involves prioritising remuneration for urgently needed and highly skilled talent while balancing the need to increase the remuneration of ordinary employees. These provisions reflect China’s policy priority of stimulating its innovation and technology industries.

Lastly, Article 58 sets a minimum ratio for performance-based pay that distinguishes China’s proposed remuneration requirements from other CG Codes in the region: at least half of the combined base salary and performance-based pay for directors and senior executives should be performance-based.

Notable alignments with China’s updated Company Law and other regulations

• Shareholder value: Article 10 requires issuers to proactively enhance shareholder value, particularly emphasising cash dividend policies. Specifically, issuers are encouraged to increase the frequency of cash dividend payouts when conditions for profit distribution are met.

• Independent directors: Several amendments align with the 2023 regulation on independent directors (INEDs). Regarding independence criteria, the draft Code adds that INEDs must not have any direct or indirect interests with controlling shareholders (Article 41) nor hold any other positions at the company besides independent directorships (Articles 40). Article 43 further specifies INEDs’ responsibilities, requiring them to actively participate in board decision-making process, provide checks and balances and offer professional advice. Moreover, Article 17 requires the use of cumulative voting when electing two or more INEDs.

• Audit committee and other functional committees: Article 45 incorporates supervisory board powers into the responsibilities of the audit committee, aligning with the CSRC’s requirement for listed companies to phase out supervisory boards by 1 January 2026. This represents a positive change since supervisory boards have long been regarded as an ineffective layer of oversight. Meanwhile, Article 44 further clarifies the composition of the audit committee: it should consist of three or more members who do not hold senior management positions.

Additionally, Article 47 and Article 48 further clarify the responsibilities of the nomination and remuneration committees, respectively, in line with the CSRC’s existing regulations.

• Director elections: Article 17 requires cumulative voting in two scenarios: (1) for the election of directors in companies where a single shareholder and persons acting in concert hold 30% or more of the shares (unchanged provision); or 2) when electing two or more INEDs (newly added provision). Additionally, Article 17 now encourages the use of competitive elections to implement cumulative voting more effectively.

• Sustainability reporting: The revised Article 99 delegates requirements for sustainability reporting to the stock exchanges: “Listed companies publish sustainability reports in accordance with the regulations of the stock exchanges”. The original Chinese text lacks prescriptive terms such as “may” or “shall”, reflecting the exchanges’ differing requirements. Currently, only leading companies listed on the main and growth boards of the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, as well as dual-listed issuers, are required to comply with the climate reporting rules introduced by the three stock exchanges in April 2024.

Stones left unturned

Despite widespread amendments, there are some areas where regulators appear to have hesitated to make changes. Below are the key areas that remain unchanged in the draft CG Code.

• Transparency over the Party committee: Article 5, which addresses the role of the Party organisation/committee, has been included in the opening chapter of the CG Code since 2018. However, the current draft of the amended CG Code still does not require disclosure of the workings of the Party committee. ACGA has previously advocated for annual disclosure of the Party committee’s on its membership, structure and major activities during the year, which would provide greater transparency and illuminate this distinctive element of China’s CG system. (8) Ideally, such disclosure is presented as a standalone report, akin to the board’s annual working report. Alternatively, a detailed narrative in the corporate governance section of the annual report would also be helpful.

• Investor stewardship: The chapter on institutional investors remains largely intact, except that the reference to supervisors has been removed from Article 83. This is a missed opportunity; we believe investor stewardship should be a more active force in advancing corporate governance in China. For example, Article 83 does not explicitly identify communication or engagement as a means for investors to improve corporate governance. It is essential to explicitly recognise investor communication as an engagement tool. The CG codes in Australia, Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia all emphasise investor-company dialogue. Directly articulating an expectation for independent directors to communicate directly with investors in the CG Code would set a new bar across the region and empower directors to engage with shareholders. This may appear ambitious, but should in actuality be a natural extension of Article 43, which addresses the role of independent directors and explicitly requires INEDs to protect the interests of “the company and all of its shareholders.”

• Board diversity: The requirement on board diversity in Article 31 is still limited to just 11 Chinese characters, translated as “Diversity of board members is encouraged”. (9) This provision is behind the curve in the region and could be strengthened. (10) In the Greater China chapter of CG Watch 2023, we highlighted a lack of credible board diversity policies among the 15 large A-share companies. As a starting point, listed companies could be encouraged to develop a board diversity policy.

Further areas for future development

• Shareholder protection in RPTs and change of control transactions: While the draft Code strengthens the board’s oversight of RPTs, we recommend further enhancements, including the establishment a special committee led by independent directors to review major RPTs. We also suggest requiring independent fairness opinions for change of control transactions involving controlling shareholders.

• Sustainability reporting: The stock exchanges’ climate reporting rules are still currently based on TCFD. (11) We recommend gradually aligning these rules with ISSB standards. In May 2025, China’s Ministry of Finance released the Exposure Draft of the “Sustainability Disclosure Standard for Business Enterprises No.1 – Climate Standard (Trial)”, which substantially converges with IFRS S2. (12)

• Board independence and expertise. Given the prevalence of concentrated ownership in China, further strengthening the influence and expertise of independent directors on the board would be beneficial.

Overall, the draft CG Code marks a notable step forward, driven by close alignment with the 2024 Company Law and related regulations. The updated framework tightens oversight of directors, senior executives, controlling shareholders and de facto controllers, and moves remuneration practices towards international norms. Greater alignment with global standards on investor stewardship, board diversity, shareholder protection, sustainability reporting and transparency—especially concerning the Party committee—will be needed to further elevate China’s CG standards.

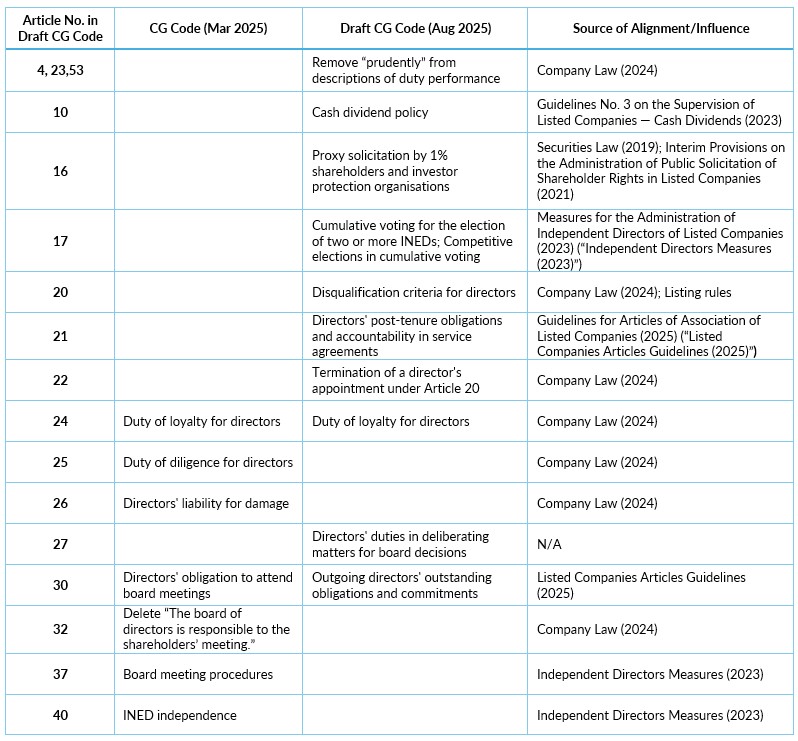

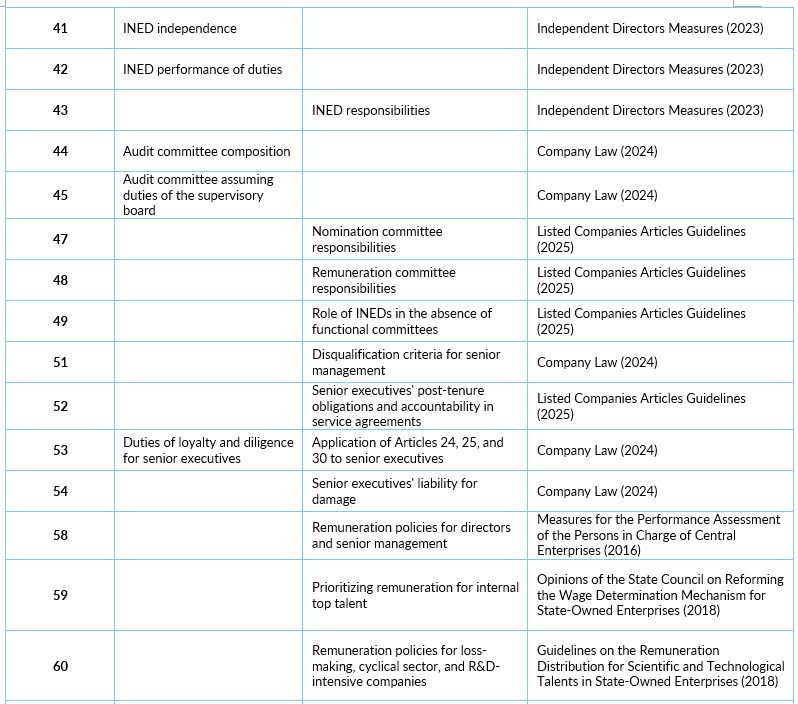

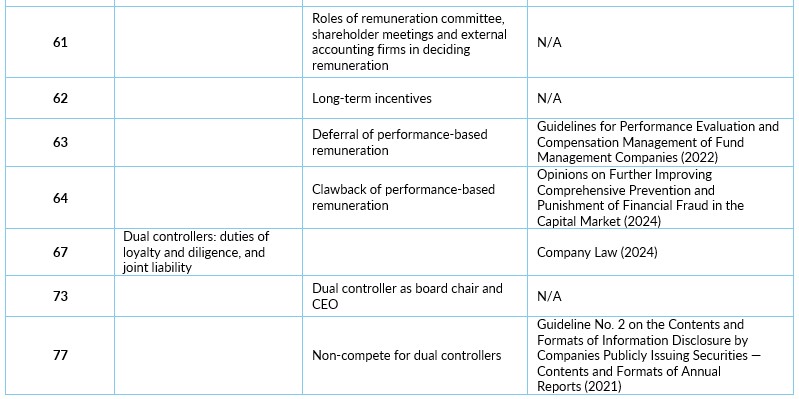

Appendix: Key Amendments in China’s Draft CG Code and Sources of Alignment/Influence

Footnotes:

1. The draft and its explanatory notes are currently available in Chinese only: http://www.csrc.gov.cn/csrc/c101981/c7573403/content.shtml

2. See ACGA’s submission on the 2018 draft CG Code here: https://www.acga-asia.org/advocacy-detail.php?id=149&date2=2018&sk=&sa=

3. See ACGA’s analysis of China’s new blueprint for modernising its corporate system: https://www.acga-asia.org/blog-detail.php?date=2025&cid=&country=&id=103

4. Unlike Korea’s recent Commercial Code amendments, China’s directors fiduciary duty is only to the company.

5. The original text in the Company Law uses the vague term “others” here without offering a clear definition.

6. The draft CG Code does not specify which industries are considered cyclical. For reference, the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s SSE Cyclical Industry 50 Index includes real estate, finance and insurance, mining, transportation and warehousing as cyclical sectors.

7. The CG codes in other major markets are either less prescriptive on pay ratios or do not address this issue (e.g. the CG Codes in Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong). For example, the UK CG Code (2024) only requires the board to review workforce remuneration, while Australia’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations notes in a footnote that individual employee remuneration packages are determined by management.

8. See ACGA’s special report, “Awakening Governance: The evolution of corporate governance in China”, available at: https://www.acga-asia.org/thematic-research-detail.php?id=158

9. The original Chinese text is “鼓励董事会成员的多元化”.

10. For instance, Hong Kong’s updated CG Code mandates an annual review of the implementation of board diversity policies and requires the appointment of at least one female director to the nomination committee on a comply-or-explain basis. Earlier, in 2022, the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing (HKEX) banned single-gender boards. As of the end of June 2025, fewer than 10 issuers on HKEX had all-male boards.

11. See ACGA’s analysis: https://www.acga-asia.org/blog-detail.php?date=2024&cid=&country=&id=80

12.See ACGA’s response to this Exposure Draft: https://www.acga-asia.org/advocacy-list.php?cid=1&country=3

Download File Disclaimer

In addition to the ACGA website disclaimer access to the "Members' Area" of the ACGA website is subject to the general disclaimer and content attribution statements below.

General Disclaimer

By logging into our Members' Area you acknowledge that all materials displayed on the site or made available for download are for the exclusive use of ACGA members. You may not share the content with parties outside of your organisation.

Content Attribution

The copyright ownership of all material on our website belongs to ACGA. Should you wish to use any materials in the course of your corporate research, including directly quoting or paraphrasing sections, reprinting, reproducing or the like, we request that you give proper acknowledgement to ACGA and share a copy with us. Please email irina@acga-asia.org.

Lake Wang

Lake Wang