Corruption just got easier in Indonesia

by Christopher Leahy, ACGA

Recent political machinations have emasculated Indonesia’s once-feared anti-corruption commission and its future looks bleak, writes Chris Leahy.

Formed amid much scepticism in 2003 under the administration of former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, the Corruption Eradication Commission, known locally by its acronym, the KPK, surprised everyone by early and significant anti-corruption successes, forging a relationship for competence, impartiality and ruthless efficacy.

Major targets felled included several sitting politicians, senior law enforcement and government civil servants as well as private sector tycoons. Notable KPK scalps included then police chief Susno Duadji jailed in 2009 for corruption and abuse of power, former Speaker of the House of Representatives Setya Novanto, who was jailed for 15 years in April 2018 for siphoning off US$170m of state funds, and Minister for Youth and Sports, Andi Mallarangeng, who completed a four-year prison sentence for graft in July 2017.

Initially armed with powers to wiretap suspects and conduct extensive surveillance, pursuing investigations and prosecutions independently of the police and Attorney General’s Office, the KPK chose its targets carefully with stunning results. Since 2003, the KPK has successfully prosecuted more than 500 cases, losing just one.

The sky high conviction rate might seem suspicious but the KPK proved extremely effective. Too effective as it turned out, and that sole acquittal likely became a turning point for the KPK. In July 2019, the Supreme Court overturned on final appeal the conviction of Syafruddin Arsyad Temenggung, the former head of Indonesia’s Bank Restructuring Agency and one of the KPK’s biggest wins. Syafruddin had been jailed in September 2018 in a US$300m graft case involving Indonesian tycoon Sjamsul Nursalim. The Jakarta Corruption Court found Syafruddin to have discharged the owner of Bank Dagang Negara Indonesia (BDNI) from repaying government funds dispersed following the Asian Financial Crisis. An appeal court in January 2019 upheld the original decision and even increased Syafruddin’s custodial sentence from 13 to 15 years. However in a controversial split decision, the Supreme Court overturned the conviction. It proved to be a watershed moment, and suspicions arose that a politically-inspired takedown of the KPK was underway.

During President Joko Widowo’s second term, facing pressure from within his own Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) and in particular, key supporter, Megawati Soekarnoputri (the daughter of former President Sukarno) Jokowi hurriedly signed a controversial new KPK law in October 2019. Megawati’s eldest son, Muhammad Rizky Pratama, known as Tamtam, had been named a suspect by the KPK in a bribery case in November 2019, which is believed to have been instrumental in triggering the political backlash against the KPK.

Jokowi’s new law significantly circumscribed the KPK’s powers and independence by making it answerable to Parliament via a new supervisory board and effectively removing its independent powers of surveillance and investigation. It also presaged the transfer of all KPK staff to the civil service, a process completed in October 2021. Previously, KPK staff and commissioners were regarded as independent and free from government interference.

To add insult to injury, in May 2021, under the supervision of its new Chair, Firli Bahuri, an active police chief, the KPK ran tests for all KPK employees ahead of their transfer to the civil service. Known as the civic knowledge test, the KPK said the test was simply aimed at assessing KPK employees' allegiance to the national ideology of “Pancasila”, a foundational philosophy of Indonesia, based on five guiding principles. The test however, was marred by controversial questioning and poor administration. Critics cited the 75 employees who failed the test as being singled out by the new politicized KPK as troublemakers and unlikely to tow the new political line.

On 10 June 2021, Komnas HAM, the Indonesian Commission on Human Rights announced an investigation into allegations by KPK employees of abuse and bias as a result of the fallout from the tests.

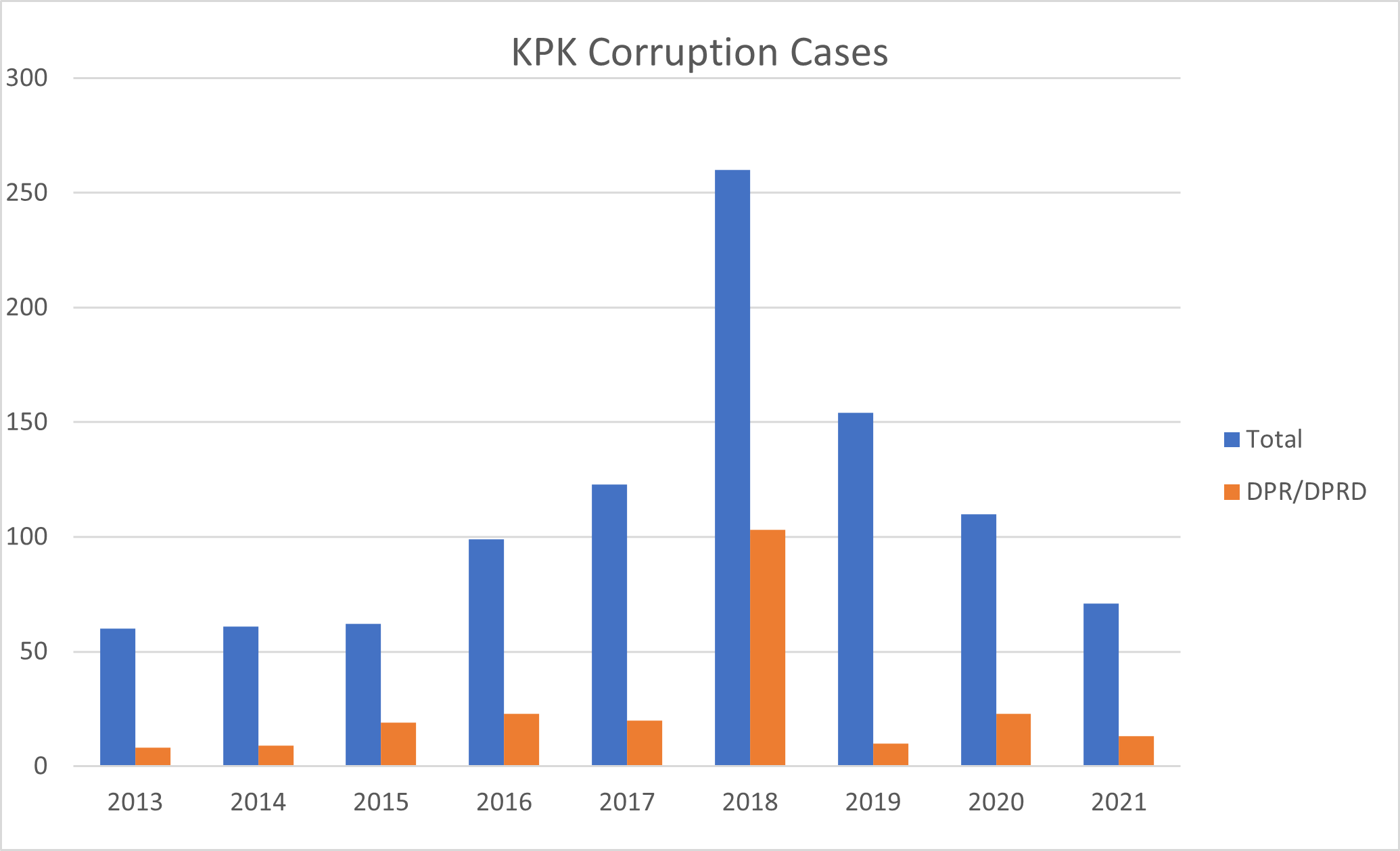

Data from the KPK clearly demonstrates the effect of political interference on its activities, with a sharp drop in the number of cases prosecuted in recent years, particularly with respect to elected politicians (see the table below).

Note: DPR refers to the People’s Representative Council, the lower house of the People’s consultative Assemly; and DPRD refers to the Jakarta Regional People’s Representative Council, the legislature of the province of Jakarta.

Further evidence of the erosion of Indonesia’s fight against corruption came in August 2021, when the KPK lost its case against Indonesian tycoon Samin Tan. Head of coal miner PT Borneo Lumbung Energi & Metal, Tan was acquitted of bribery by the Jakarta Corruption Court. A former associate of Aburizal Bakrie, patriarch of the Bakrie Group conglomerate, and embroiled in the acrimonious investor dispute at London-listed coal miner Bumi plc (now known as Asia Resources Minerals), Tan was accused in 2019 of bribing politician and energy ministry official, Eni Maulani Saragih with IDR5 billion ( around US$475,000) to help secure ministry approval for an extension of a coal fired power plant concession held by Tan’s company, Asmindo Koalindo Tuhup.

Tan evaded arrest and fled but was finally arrested in 2020. The KPK charged him under Article 5.1 of Indonesia’s 2001 Anti-Corruption Law with giving money to Saragih in exchange for help in lobbying the energy minister. Despite hundreds of successful prosecutions and years of clear legal precedent, the three-judge court acquitted Tan by reinterpreting the Anti-Corruption Law. Head judge, Panji Surono claimed a clear distinction between bribery and gratification, opining that Tan did not bribe Saragih, he only provided gratification, which, said Panji, only involves wrongdoing by the receiver of money, not the giver. Via such tautological gymnastics, Tan was acquitted as having done nothing wrong illegally. The KPK filed an appeal against the acquittal in September 2021.

Indonesia is rapidly heading in the wrong direction in the fight against endemic corruption. Rumours are emerging in Jakarta of increasing political graft, including vast sums made from the country’s tragically handled Covid 19 response. Indonesia’s score in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions index fell from 40 in 2019 to 37 and it came last in our latest CG Watch survey. Absent meaningful reform, for which there is no political appetite, the KPK ‘s emasculation is only likely to make future scores worse.

Download File Disclaimer

In addition to the ACGA website disclaimer access to the "Members' Area" of the ACGA website is subject to the general disclaimer and content attribution statements below.

General Disclaimer

By logging into our Members' Area you acknowledge that all materials displayed on the site or made available for download are for the exclusive use of ACGA members. You may not share the content with parties outside of your organisation.

Content Attribution

The copyright ownership of all material on our website belongs to ACGA. Should you wish to use any materials in the course of your corporate research, including directly quoting or paraphrasing sections, reprinting, reproducing or the like, we request that you give proper acknowledgement to ACGA and share a copy with us. Please email irina@acga-asia.org.